THE PAPER BOAT

Date: 1989 – 1990

Location: Glasgow, London, New York, Antwerp

Type: sculpture, installation, performance

Material: Paper?

Length: 80ft

Height: 28ft

Width: 18ft

The Paper Boat Song

George Wyllie: Reflections from a Paper Boat

A paper boat confounded the prevailing winds and wisped its delicate Atlantic way from Scotland to, would you believe, the North Cove Harbour down by Battery Park City. It drifted past Liberty, and was crisp with anticipation, for it was mid-July and its happy compass had delivered it safely to America. God and Neptune be praised! On its stern – no one knows which, were the letters ‘QM’ – and no one knew exactly what they meant but it didn’t stop everyone from guessing that they meant something.

A paper boat confounded the prevailing winds and wisped its delicate Atlantic way from Scotland to, would you believe, the North Cove Harbour down by Battery Park City. It drifted past Liberty, and was crisp with anticipation, for it was mid-July and its happy compass had delivered it safely to America. God and Neptune be praised! On its stern – no one knows which, were the letters ‘QM’ – and no one knew exactly what they meant but it didn’t stop everyone from guessing that they meant something.

It appears that the delicate craft was built in Glasgow on the River Clyde for the Origami Line whose president said that it had saved his company from folding up. Other Clyde-built ships were the Queen Mary, the Queen Elizabeth and the QE2. Could the letters ‘QM’ mean ‘Queen Mary’? In Scotland the heady days of big shipbuilding are gone. Clyde shipbuilders now wield scissors, wear trainers, and have cut out smoking at work. They are building ‘paper boats’.

Their broad Scottish boast is that the ‘QM’ is the biggest in the world. It was folded up carefully from a sheet of a secret sort of paper measuring 120 ft x 80 ft. The needed a space the size of a football field to do this and a day when it wasn’t windy. No technical details have been revealed, but it is said to be driven by a powerful question-mark. Nowadays the Clyde men keep their paperwork close to their chests for they were once too generous with their knowhow, and now the rest of the world builds, ships and they don’t. By building The Paper Boat it would be said that they have turned over a new leaf.

‘QM’ was pushed into the ocean off the west of Scotland where, quite naturally, it entered a Scotch mist. It was lucky to be offered pilotage by an albatross who said it knew the way to New York. Half-way across, The Paper Boat saw some icebergs, and mistaking them for other paper boats, meandered off-course to say “Hi!” It was not a warm relationship, but this deviation took ‘QM’ north where it got dirtied by a slick seeping through from Alaska. Meanwhile its Captain and crew flew over it on Flight BA172 to JFK and looked down on it to check its course. They felt reassured when the albatross pecked at the Boeing’s window about one hundred sea miles east off Nantucket. Below, the ‘QM’ looked resplendent except for the Alaskan oil along its waterline. Two days later she entered the Hudson River at dead of night, and her captain was there to hook her ashore with his walking stick. This happened at the old heli-pad at Battery Park, and the idea was to scrub off the sludge and freshen up with hot steam so as to look good for the big occasion.

The big occasion was to berth at the World Financial Center where ‘QM’ was to deliver greeting to America as declared on its manifest – and also a wee bit of cargo. Someone said that the vessel was carrying the conscience for capitalism. The crew wondered if they had heard right.

The albatross had sloped off at Nantucket as it was only interested in crossing oceans and consequently The Paper Boat nearly lost it way. In the inclement weather it thought Lower Manhattan was Anchorage, Alaska. Luckily three observant seagulls came to the rescue and flew overhead to line her up for a precise entrance into North Cove Harbour. The Captain hailed an assembly of New World inhabitants leaning against a long quote from Walt Whitman, and they hailed back that this was indeed New York. It was a poetic moment.

The Captain immediately produced his ukulele and sang a much-needed sea shanty. His tuneful greeting was reinforced by no less than four Scottish bagpipers and a display of the powerful question-mark – it all seemed to mean something. The Captain rowed ashore in his golden dinghy, taking his golden suitcase with him and the wee bit of cargo. The display of gold was not intended to be brash – merely in defence in the dazzle of the World Financial Center. After a short exhibition of fancy rowing, the Captain clambered on to the marble dock to be met by no less than two kilted drummers, and was marched off to meet the welcoming dignitaries. He remarked afterwards that it had an uneasy touch of The French Revolution about it, but does not wish to dwell on this point. Those assembled to receive him held high office in New York and in the world of the World Financial Center, and in his own part of parts beyond the seas, namely the UK. Greetings were made to one another, and it was the same with speeches.

The Captain then produced the wee bit of cargo and said it was a ‘Spire’. It was a simple device comprising of a long thin rod with a stone secured at one end. The upper end of the rod was moved by the wind and it was counterbalanced at its lower end by the stone helped a lot by gravity. It swayed like a mast, for it was secured upright in a gimbal – a simple balancing device more to do with sailors than bankers. The Captain said the ‘Spire’ was a portable sculpture designed to celebrate the place on which it stands and beyond that, its importance was of no importance and that it was really for the planet, for: “air stone and the equilibrium of understanding”.

He also mentioned that the original native inhabitants of these shores would have readily understood this and no one could think quickly enough to disagree. It seemed it was an ecological statement not commensurate with the state of the nearby Hudson. The captain then opened his golden suitcase and displayed the log-book of The Paper Boat. In it was recorded the QM’s manifest, the purpose of which was to make things plain; clear; apparent; beyond doubt; evident; open; visible. The log was to be placed in a prominent place for perusal in in the World Financial Center to make things particularly plain to a particular type of public.

Conscious that The Paper Boats’s port of call was the naval button of the world of finance, it had seemed to the Captain, namely George Wyllie, a Scottish Scul?tor that there was something requiring to be made plain; clear; evident; – and so on. The Captain, braced by trans-Atlantic energy, made his report.

“Greetings!” – to all whom these presents shall come… take note that this year 1990 is the bi-centenary of Adam Smith, author of the classic rules-book for capitalism, The Wealth of Nations, and that I, Master of this paper boat, do hereby deliver this manifest. Here this…. Adam Smith once Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow, who breathed the good air of Scotland, would never have wished upon any society the iniquities presently engendered by the system he expounded. Be aware that I, a Scottish captain, sailing out of the Port of Glasgow, and born in that place, do hereby swear by its air and its stones and the good nature of its people, that Adam Smith earnestly professed that another volume of his philosophy be applied as equal to his Wealth of Nations. Your own good Professor Heilbrouner right here in New York, has already understood the correct necessity to publish them together in The ESSENTIAL Adam Smith. As a Scot, a bit calvinistic, sparingly subversive, five feet eight inches, stocky, fairly ancient, emerging here from a Brigadoon mist with nary claymore, I claim due entitlement to deliver this neglected document for the benefit of your attention. Dear American friends, it is with warm pleasure that I present for the enlightenment of us all, Adam Smith’s OTHER BOOK – The fifty per cent of his good intentions left sleeping down below. It is not so much that we have been living a lie since 1790, but rather that we have been living an omission. Boats should – but probably won’t, be rocked by belated awareness of Adam Smith’s pride in this conscience of capitalism. We may need and be glad of it yet – his Theory of Moral Sentiments. Take heed of the first sentence.

How selfish so ever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and renders their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of see it.

Having made his report, The Captain felt hungry for the official lunch where he was accorded the great indigestive respect that accompanies wariness. Notwithstanding, he was able to knock-off his food and the essential matter of morality in the same way as any profundity is understated in dear old Glasgow town.

Could it be the QM stands for Question Mark?

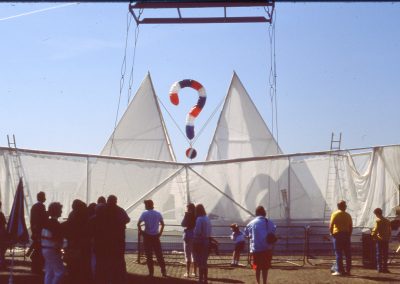

George’s dismay at the virtual disappearance of Glasgow’s once mighty shipbuilding industry drove his Paper Boat. Fusing engineering, street theatre, visual art, performance and music in one provocatively playful package, the boat had a steel frame clad in sheets of plastic and gauze Velcroed together, which opened to reveal a viewing platform.

George’s dismay at the virtual disappearance of Glasgow’s once mighty shipbuilding industry drove his Paper Boat. Fusing engineering, street theatre, visual art, performance and music in one provocatively playful package, the boat had a steel frame clad in sheets of plastic and gauze Velcroed together, which opened to reveal a viewing platform.

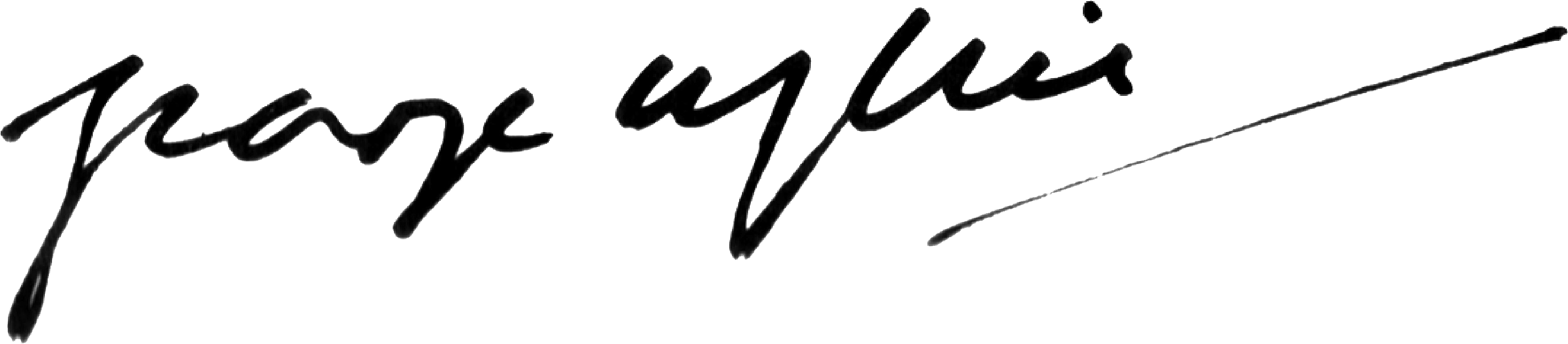

There was, naturally, an elevating question mark inside, but this time George wanted the simplistic beauty of the sculpture to be appreciated in equal measure to the political content. He was heavily influenced by French poet Arthur Rimbaud’s “Drunken Boat” poem, the first line of which describes a something or someone in a boat “floating down unconcerned rivers” being “steered by the Haulers”.

The narrator describes gliding down calm rivers to tide water, and then for ten nights being tossed about by the tumultuous waters of the open sea. The experience is a joyful one, and at the end the speaker has a feeling of freedom and purification. The Paper Boat carried the initials “QM”, but George admitted later that “we were never sure what QM stood for. It’s always good not to know something about what you’re doing. We had notions it might mean Queen Mary or Question Mark or Questioning Mind”. He made the boat in collaboration with Harry Finlay of the Greenock Welding Company. The two men worked together on Straw Locomotive but had enjoyed a fruitful relationship going back to the 1970s.

In order to be legally seaworthy, George tested the 78ft-long Paper Boat at the Denny Tank in Dumbarton. This was the test facility where designs for the massive Clyde-built ships were undertaken. She was then certified with Lloyd’s to complete the paperwork side.

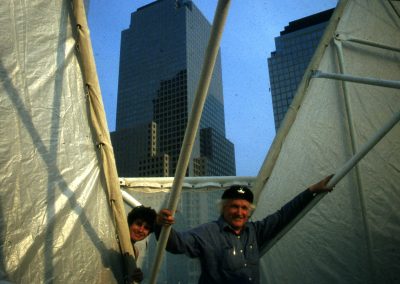

The launch of the pride of The Origami Line (with the letters QM on her hull) took place on a beautiful sunny day on 6 May 1989 in front of a large crowd, and echoed the celebratory launches which once routinely took place on shipyards on the banks of the Clyde. (The title was a nod to the Japanese art of paper folding and a subliminal reference to the time he spent in Japan during the war.) There was even a blessing by industrial chaplain Revd Norman Orr and a naming ceremony by the writer Naomi Mitchison. Accompanied by the Da Capo Choir from Greenock, George, in his pristine white boiler suit and captain’s hat, performed “a corny wee tune, a paddle-steamer song” which he’d composed for the occasion. It begins:

So now that we’re building a Paper Boat,

A Paper Boat Paper Boat

don’t-be-surprised-at-the-way-we-vote.

(We’re going to build a big Paper Boat,

A Paper Boat Paper Boat

folded up carefully so it can float

– but not what a ship used to be.

George maintained that he wasn’t nostalgic about shipbuilding, but rather for the skills and the spirit that went into it, and the transcending of the tough conditions of the shipyards. Where was this energy now? he asked, as his “paper” boat travelled to London and made a splash there. In Murray Grigor’s The Why?s Man, which also documented his Paper Boat project, he quipped that “on paper” he was the only shipbuilder left on the Clyde.

The idea of social sculpture, a concept mooted by his guru, Joseph Beuys, was the major driving force behind both Straw Locomotive and Paper Boat. Paper Boat referenced Joseph Beuys’ idea of a journey, one that took it from Glasgow to Liverpool and on to London, New York, Antwerp, Dumfries and the east coast of Scotland.

In his art, which encompassed drawing, sculpture, painting and performance, Joseph Beuys wanted to take both himself and the audience on a literal and figurative journey which would transform their idea of society. There was also a strong aspect of the healing effect of art in all of his work. He often incorporated deeply personal motifs into his work, such as animal fat and felt, which had profound meaning to him. Both organic materials related to his wartime experience serving with the Luftwaffe, and it was his conviction that if he felt a profound connection, then the audience would feel it too. George, himself an ex-serviceman – also profoundly affected by his time in the Royal Navy – espoused this idea wholeheartedly.

George received support for his Paper Boat events from Beck’s Beer, who even produced limited edition Paper Boat-labelled bottles, part of a long-running Beck’s Art Labels project, which started in 1987. The first to be featured in the series were Gilbert & George, and since then the list has grown to include names such as Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons and Andy Warhol.

In September 1989, Paper Boat travelled to London, and on Thames Day (9 September) it sailed under Tower Bridge to the Houses of Parliament. As a patriotic gesture, the question mark inside the Paper Boat this time was red, white and blue. George’s prime aim in London was to draw attention to Thatcher’s policies, including the privatisation of the shipbuilding industry. In order to ensure that Tower Bridge had to be opened, a tall mast was added, flying the Scottish Saltire. Traffic was stopped, the bridge was opened and the Paper Boat sailed through and was moored opposite the Palace of Westminster. The questions, as well as the bridge, had been raised. But George was not happy. According to his friend and frequent helpmate Pete Searle, George cried when he discovered Thatcher was not there to see the boat opening up to reveal a giant question mark. As always, there was a little detail which kept the project grounded; George had borrowed the Union Jack flag which flew on the Paper Boat from the Inverkip Scouts. (His nephew Alistair, like his father Banks, was, and remains, a key figure in the scouting movement.)

The following summer, in July 1990, Paper Boat sailed up the Hudson and into the World Financial Center in New York accompanied, to George’s delight, by the Duke Ellington Band. On docking, George sang the Paper Boat Song accompanying himself on the ukulele, and then, as the question mark was revealed, four Scottish pipers played. He took a spire with him as he went ashore to celebrate the “place in which it stood”. He then opened a golden suitcase and took out the “ship’s log”. The purpose of the Paper Boat, George told bystanders, was to make things “plain; clear; open and visible”, and he added that he intended to do just that. The boat created a real splash by making it onto the front page of the Wall Street Journal. The headline on 16 July 1990 read: “Laugh You May, but Remember It’s Floating and the Titanic Isn’t”. For its New York jaunt, George had included notations inside the boat from Scots economist Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments. The newspaper wrote: “Mr Wyllie says Wall Street has forgotten The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Mr Smith’s companion [to The Wealth of Nations] treatise on conscience and morality.” George’s timing was important as the bicentenary of Smith’s classic text on capitalism, The Wealth of Nations, was celebrated in 1990. He then read the first sentence from Theory of Moral Sentiments.

How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.

The boat was taken on many journeys, but eventually George sent it to a shipyard at Inverkeithing and had it broken up like a real liner. He recycled the material and made a giant goose, which he called “Truce Goose”, for a project in 1993 about a compromise between farmers and conservationists over the thousands of geese which consumed huge amounts of grass on the Hebridean island of Islay every year.

From Arrivals and Sailings: The Making of George Wyllie by Louise Wyllie and Jan Patience